Freedom, Fairness, and Regulation

Albert Beardow.

In everyday speech and even in the media, the concepts of free trade, free markets and light regulation are often used interchangeably, with little appreciation for the key differences between them. Both their supporters and detractors see them as part of a laissez-faire package grounded solely in the unwavering principle of individual freedom. Yet the rationales for these concepts as the basis for economic life are quite distinct, and need not draw only on a moral belief in human freedom, but empirical observations and broader notions of fairness and equality before the law.

Free Trade

Free trade is the notion that international trade should be

allowed without tariffs or restrictions – or taken in the broadest sense, that

trade should be permitted between humans on the same terms regardless of their

membership of different nations or any other groups.

| Canary Wharf Skyline (photo by David Iliff) |

The early advocates of free trade - Adam Smith and David

Ricardo prominent among them – tended to argue primarily in terms of its

empirical results – comparative advantage and fostering competitiveness. Whilst

this is doubtless a significant (though oft disputed) part of the rationale

behind free trade, I will not shy from saying that for me it is the moral

argument that is most important.

There are two primary ways in which restrictions on free

trade violate ethical notions of human freedom and dignity. The first is to

subordinate the will of the individual to that of the “community”, membership

of which is rarely chosen but bestowed through the serendipity of birth. In

spite of what many opposed to free trade say, it is impossible to “force” free

trade on a person – rather the opposite, that force can only be used to deny a

person the right to free trade. This is perhaps not so much of a problem for

those “collectivists” who treat collectives as bodies with superior moral

standing to individuals.

Most collectivists (at least in the West) are less inclined

to dispose of the moral concept of human equality. Yet restrictions on free

trade do exactly that, for the “community” in question is not mankind as a

whole, but rather the nation. Given that nations have been for the most part

arbitrarily defined through the whims of history, mostly by kings and

conquerors long dead, it is difficult to see how these can be given an

independent moral standing. If members of a different (perhaps poorer) nation

are denied the same rights in their relationship with you as those within your

own nation, in what way can it be said that all humans have an equal standing

in terms of social justice? Some humans are then clearly more equal than

others. One need only observe how quickly protectionist rhetoric introduces the

notion of “them” as opposed to “us” to see how the rights and desires of others

are soon devalued.

Free Market

If free trade deals with the question of “who”, then the free

market deals with the “how”. The core notion of the free market is that prices

and the distribution of goods should be set by supply and demand, and not by

fiat.

There is, of course, considerable debate over the definition

of the term, with many contending that a free market means freedom solely from

government interference, and that a free market is equivalent to laissez-faire. However, I would tend to

agree with the British classical economists from Smith onwards, who argued that

it does not matter whose fiat dictates prices – and as such, monopolistic or

monopsonistic markets cannot be characterised as truly free. For supply and

demand to work in determining price, competition on both sides is vital, and

thus a free market entails both a competitive system and the open access to

markets that facilitates this.

| Afghan market |

Moral arguments in favour of human freedom are less

convincing if used on their own to justify free markets. Even the most ardent

libertarians would deny, for example, that it were a morally just situation if

a man dying of thirst freely gave up his life’s savings in exchange for water

from a monopolist provider. The crucial argument supporting the free market is

empiricist in nature, and relates directly to the competitive system, and its

building of what Hayek called “spontaneous order”.

Freely set prices are important because they incorporate all

the various pieces of disperse knowledge that different actors in an economy

have – knowledge that no expert alone could possibly have access to. These

prices then guide resources to be allocated in desirable ways for society – to

overcome shortages, improve quality, and identify new demands. The beauty of a

free market system is its ability to spontaneously deal with the very

complexity that socialists believe makes planning desirable, but which makes

planning ultimately hopeless.

Regulation

A free market need not be totally absent from regulation to

remain free. It is hard to argue that a well thought out regulation to protect

workers’ or consumers’ safety, for example, would on its own distort the method

by which prices are set. The damage done by regulations instead arises

primarily from two sources: inhibited innovation due to precautionary

restrictions, and the costs of excessive complexity.

Economies grow through a process of trial and error, through

the success and failure of new business ideas, scientific endeavours and

technological breakthroughs. It is in the realm of the untried and untested

that the greatest prospects for growth are to be found. It should therefore

follow naturally that regulations which prevent (or at least delay) new

endeavours are a deterrent to progress. There is, of course, a more profound

debate to be had here about the extent to which society wants to risk the

uncertainties and possible dangers that come with new developments (which I

will write about in more detail in a future post). Needless to say, of course,

that societies which opt for a stationary state always fail to satisfy

underlying desires for prosperity and opportunity, and are thus on the road to

decline.

|

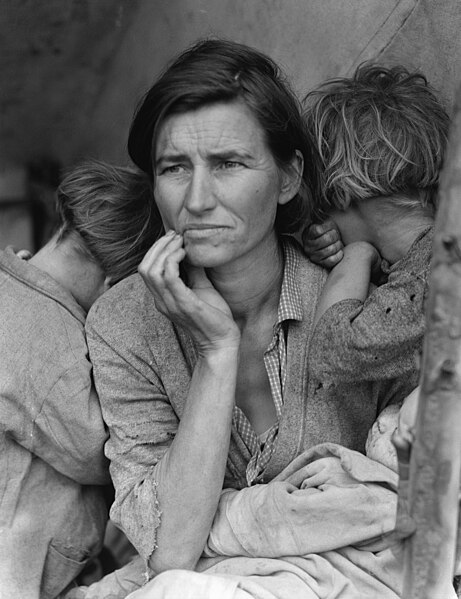

| Lange's 'Migrant Mother', symbol of the Great Depression |

The most damaging aspect of this complexity is that its

effects are not equally spread – the huge budgets and compliance departments of

large and powerful corporations are well equipped to deal with these burdens.

Not so the small business or aspiring entrepreneur. By adding an additional

hurdle to entry, large companies reap the benefits of less competition (and I

am here not even mentioning the hand they have in writing these regulations).

Yet the biggest beneficiaries are, of course, the lawyers, accountants and

bureaucrats who thrive on complexity.

Rather than arguing blindly over a false dichotomy between

regulation and de-regulation, I would like to see more discussion about the

fairness of regulations. Though President Obama recently talked about the need

for fairer regulations, in asking only whether regulations benefit the rich

over the poor he misses the crucial point. We should instead be asking whether they

favour any special interests at all over the community as a whole. For the

reasons above, fairness and simplicity go hand-in-hand – and rather than simply

asking whether regulations favour the poor or the rich, we should recognise

that an excessive number of regulations ultimately only favours the powerful.

No comments:

Post a Comment